In Sweden, decarbonisation in the building sector is one step ahead

10 min

The country has significantly reduced its CO2 emissions from building construction and energy consumption. It is now a true model for Europe.

Sweden, a country that borders on the Arctic Circle, has long mastered the art of sheltering from the cold. Could this be one of the reasons why the Scandinavian kingdom is now so exemplary in terms of building energy consumption? Construction, insulation, heating... The decarbonisation of this sector is unquestionably well ahead of its European neighbours.

And the stakes are high: the building sector is generally a heavyweight in greenhouse gas emissions. According to a report by the French High Council on Climate, published in November 2020, it accounts for more than a third of CO2 emissions in the European Union, and more than a quarter in France. It is therefore a key lever for combating climate change and achieving carbon neutrality*, which the EU is aiming for in 2050. Another report, this time from the UN, stated at the end of 2020 that to achieve this goal, “direct** CO2 emissions from the sector must fall by 50% by 2030, and indirect emissions by 60%”. A major breakthrough, in short.

⅓

The building sector accounts for one third of the EU's CO2 emissions.

In Sweden, this process is already well underway. Take heating: according to the National Environment Agency, its CO2 emissions fell by 90% between 1990 and 2019, to 885,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent. That is about 2% of national emissions... How did Stockholm achieve this result? By activating two levers: energy savings and the switch to renewable energy.

Energy efficiency

As early as the 1960s, Sweden began to work on improving the energy efficiency of its buildings. According to the High Council on Climate, the country introduced demanding energy performance standards, particularly with regard to the construction of new buildings. Thick layers of insulation, triple glazing, etc. These standards are, even today, higher in Sweden than in France.

Although the country is now well ahead, it still needs to make significant efforts: only 15% of single-family homes and 5% of apartment buildings have yet to meet the BBC (low-energy building) standard. In 2020, the Swedish National Energy Renovation Strategy pointed out the urgent need to speed up this process, especially for lower-income households, who often live in less well-insulated housing. Sweden has a huge task ahead of it in the coming years: the energy renovation of “Miljonprogrammet”, a million social housing units built between 1965 and 1974. The developer and property owner Rikshem AB, which is in charge of the programme, aims to become CO2 neutral by 2030.

A healthier heating system

In parallel, Sweden set in motion an ambitious energy transition very early on. In the 1970s, faced with two oil crises, it quickly reduced its dependence on oil, relying on nuclear power, renewable energies and coal. In 1991, the Scandinavian country launched a major tax reform, introducing a carbon tax in addition to an energy tax. This tax has continued to increase ever since, reaching the particularly high price of 120 euros per tonne of CO2. It thus penalises the most emitting energies... such as coal and oil.

Another Swedish particularity is that heating networks, the first of which was built in 1948, have become widespread in cities under the aegis of municipal public companies. Initially fuelled by oil, then coal, these collective networks now rely heavily on renewable energy. About half of them are fuelled by the combustion of biomass - from the forestry industry - but also by waste incineration, heat pumps or the recovery of heat produced by industries. The result: less CO2 emissions, but also healthier and more breathable air in cities!

In Sweden, the share of oil in residential energy end-use has fallen from 72% in 1970 to 7% in 2019.

Today, 90% of buildings and nearly 20% of individual houses are connected to these heating networks. In non-connected homes, heat pumps, electricity or wood are by far the preferred energy sources for heating. In parallel, the share of oil in the residential sector's final energy use has been divided by ten, going from 72% in 1970 to 7% in 2019, according to the Swedish Environmental Agency.

Towards carbon-neutral construction?

Energy efficiency, heating... and construction. In this last area too, Sweden is making noticeable efforts. “The government has started to work on how to reduce the carbon footprint of construction machinery, which now accounts for almost 6% of the country's emissions,” explains Per Dyfvelsten, an analyst at the Swedish Energy Agency. Beyond the impact of construction equipment - which can be powered by electricity to reduce emissions - there are also large-scale projects targeting construction materials. “There are already products available that reduce the climate impact of concrete”, says Per Dyfvelsten, citing Heidelberg Cement Group: which recently announced plans to develop the first carbon-neutral cement plant. Its installation, planned for 2030, should capture 1.8 million tonnes of CO2 each year and store it deep in the rock, instead of releasing it into the atmosphere.

Another material massively used is steel. In Sweden, two steel industry giants and an electricity company joined forces in 2016 to produce carbon-free steel. They did not rely on CO2 capture and storage, but on a new industrial process, involving a colossal investment: instead of smelting the ore in coal-fired blast furnaces, they plan to use electric furnaces running on renewable energy. This decarbonisation of steel “should make it possible to reduce the emissions of steelmakers by 35 million tonnes of CO2, i.e. two thirds of the kingdom's climate footprint”, according to an article in French newspaper Le Monde.

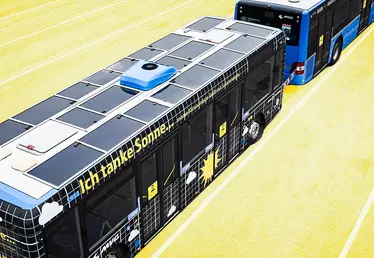

Gradually, these ambitions are becoming reality... In 2020, the first building to be certified as carbon neutral by the Sweden Green Building Council – an NGO that brings together Swedish construction companies to achieve environmental goals - was completed- a Lidl supermarket built in Visby, on the island of Gotland. No steel or decarbonised concrete here, but lots of wood, and several tricks to make this building carbon neutral, from its construction to its final use. To achieve this, emissions are kept to a minimum, for example by using more energy-efficient lamps, or by recovering heat from the building. The remaining emissions must be offset, for example by producing more renewable energy than the building consumes. The roof is therefore covered in plants... and solar panels.

* Carbon neutrality: balance between human-induced CO2 emissions and its extraction from the atmosphere.

** In this case, direct emissions are related to the use of coal, oil and gas; and indirect emissions are related to the production of electricity