Hero banner custom title

Should we eat less meat to reduce our carbon impact?

5 min

Producing meat emits methane, nitrous oxide and CO₂, three climate warming gasses- An explanation, step by step.

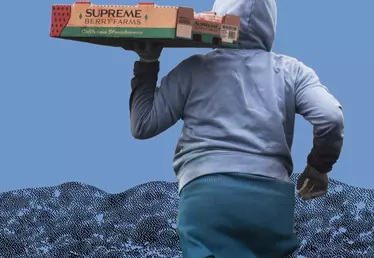

We rarely think about it when we eat a steak... And yet, eating meat is far from harmless for the climate. The livestock sector is even a major contributor to climate change: in France, it accounts for 80% of agricultural emissions, if we take into account animals and crops used to feed this sector. Yet, agriculture itself is the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in France. Where do these emissions come from, from farm to fork?

Firstly, cows and sheep burp and fart. In other words, the gastric fermentation caused by their digestion creates methane gas which, when released into the atmosphere, is a powerful greenhouse gas. This process is not without significance: this fermentation, which is natural in ruminants, accounts for half of the emissions on livestock farms. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement, according to Jean-Baptiste Dolle, head of the environment department at the Institut de l'élevage:

“We can reduce these emissions by improving animal feed, for example with flax or certain algae, or by working on cattle genetics”.

The second stage is excrement: nearly a quarter of livestock emissions come from dung and other excrement. These release methane and nitrous oxide, another greenhouse gas, which is also very warming. This can be better managed by removing the dung quickly from the buildings and storing it in tanks to prevent gas from escaping into the atmosphere. Manure can then be used in the fields as fertiliser or in anaerobic digesters to produce renewable gas - which can then be converted into heat, electricity or fuel for vehicles.

Farm autonomy

Another, more indirect, source of emissions is crops used for animal feed. According to the Institut de l'élevage, 7 to 10% of emissions come from their fertilization with nitrogenous fertilizers, which also emit nitrous oxide. “The Nitrate Directive has made it possible to reduce the use of these fertilizers, but there is still room for improvement, particularly by planting more leguminous crops, which capture and fix nitrogen in the soil”, explains Jean-Baptiste Dolle. Organic farming also makes it possible to eliminate, more radically, all nitrogenous fertilizer inputs.

As for the remaining 15% of emissions, they are made of CO2. Where does it come from? Firstly, imports of feed for livestock. And in the first place, soya, massively imported from America: Brazil, Argentina, the United States... In addition to the carbon footprint associated with its transport and processing, this crop is a major cause of deforestation, particularly in the Amazon. A deforestation that destroys biodiversity, and releases tons of CO₂ naturally stored in these forests. To avoid this scourge, one solution is to increase the autonomy of French farms, by producing the proteins needed for livestock on site: soya, rapeseed, legumes... Or at least to source them as locally as possible.

Lastly, the final source of CO₂ emissions: energy consumption within farms, particularly for tractors, and the transport of animals to slaughterhouses.

Reducing livestock

Can we reduce these emissions by improving livestock farming practices? “By playing on all levers, we can reduce our carbon impact by 20% by 2030, which will allow us to be in line with the national low-carbon strategy, says Jean-Baptiste Dolle. The aim, initially, is to get producers on board with this approach, then to go even further by 2050 with, for example, agroforestry or genetics”.

In order to meet the European Union's 2050 carbon neutrality* targets, agriculture will have to do more: it is required to reduce its emissions by 46%.

To support this effort, the Institut de l'élevage launched the Low Carbon Label in 2015. 1,300 farms have already obtained it, out of 16,000 farms committed to reducing their emissions. Thierry Bertot was one of the first farmers to take part in this “low-carbon dairy farm” programme. He keeps 90 cows, with his brother, in Normandy, near Rouen. His first carbon footprint, nearly ten years ago, already placed him below the national average, with 0.77 kg of CO₂ per liter of milk. “We have worked closely with a group of dairy farmers on energy savings, he explains. Our farm is quite self-sufficient, with a quarter of our surface area dedicated to feeding the herd, in pasture and in maize or other crops for the winter. If we want to do even better, we can plant more legumes to reduce fertilizer... and plant even more grassland”.

Why grasslands? Because they store CO₂, and therefore partly compensate for the emissions from livestock farming. Provided that they are preserved, and that they are not cultivated or artificialised after a few years... According to Cyrielle Denhartigh, in charge of agriculture at the Climate Action Network (CAN), “extensive livestock farming and the use of grazing maintain grasslands which have several benefits: carbon storage in soils, but also protection against erosion, and adaptation to climate change by creating cooler micro-climates and by naturally storing water resources”.

Even so, these grasslands will not be able to compensate for everything.

“The most important lever, if we want to have a chance of achieving our climate objectives, is to reduce livestock numbers by at least 50%”.

But, even with “decarbonised” meat, we will clearly and undeniably have to eat fewer steaks... “However, this does not mean killing off livestock farming”, continues the expert. The CAN is thus campaigning for a transition to a more sustainable model: small farms, more extensive, with more pasture, and employing more people. “It's a question of political will and support to farmers, argues Ms Denhartigh. Unfortunately, the last CAP [EU Common Agricultural Policy] missed the boat...”.

* Carbon neutrality: balance between greenhouse gas emissions and their absorption (zero net emissions).